Last week, I joined my flatmate Mandy on a Penguin Tour with the Royal Albatross Centre out on the Otago Peninsula. It was one of the cooler moments in my life, watching tiny blue penguins scurry out of the water and up to their nesting holes in the hillside. Read on for my experience and how to take your own penguin tour.

I drove out toward Taiaroa Head at dusk as the sea fog was rolling in. It was cloudy, misting, and the fog was steadily drifting lower and lower. When I arrived in the parking lot at the Royal Albatross Centre all I could hear was the sound of the seagulls. Their incessant squawking propelled me into the warmth of the visitors centre.

Mandy met me inside and handed me my bracelet that defined me as a tour participant. The last time I visited the centre, I spotted several albatross flying over the cliffs and lighthouse; today, many of those albatross have left the land for far flung islands south of New Zealand: the Auckland Islands, and the Campbell Islands, for two. As we milled around the lobby waiting for 6:30 to roll around, we wandered through the exhibits. There is a lot of information at the visitors centre, from what sort of animals live on the Otago Peninsula to the ecosystem and the geology of the area. All of this of course relates to how and why species of penguins and albatross make this region their home. At around 6:40, the tour leaders gathered us around for a short briefing on the night’s activities and etiquette.

Little blue penguins, or korora to the Maori, are the smallest penguin species. To them, we are giants. Loud, smelly, giants with things that flash. It is imperative, then, that we treat these animals with respect since we are on their land. Joel asked us to make sure we didn’t turn our camera flash on (hence why most of my photos are blurry). A bright flash into the eyes of these tiny creatures can severely disorient them to the point that they might not return home. Over time, flashes can weaken their eyes, leading to them not finding food or sensing danger as quickly, which can in turn kill a little blue penguin.

With the formalities out of the way, Joel and Ashley led the way down to the path. Almost a hundred steps lead down to a wooden platform built at the edge of the rocky beach, with bright lights shining out on to the beach and a small dirt path. We gathered along the railing and waited for a flash of blue. Penguins tend to come to shore in rafts, so we also kept our eyes peeled for a raft of darkness swimming toward shore.

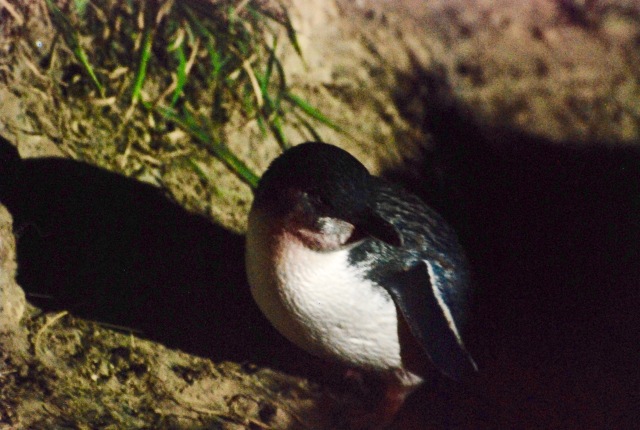

Seaweed swayed in the water on the right, prompting some false alarms for the first penguin sighting, but soon we caught a glimpse of our first one. He shot out of the water on to the rocks and shook himself to rid his fur of the excess seawater. He ducked his head and tucked his fins to his side before climbing across the rocks to the path. He seemed to take ages, the rocks almost as large as he was.

Soon, he was joined by another one, who surfed into shore the same way. They made their way to the dirt path and began to scuttle toward the grassy knolls. More penguins joined them on shore and soon the air was thick with shuffling feet and the loud insistent call of a penguin.

If you have never heard a penguin screech from right below your feet, let me share with you what that sounds like:

As the sea fog grew denser, some of our fellow watchers began to leave. Our numbers dwindled and soon Ashley made the call that it was time to go. Because the fog was so thick, a penguin can lose his or her way to the shore, and Ashley anticipated that not many more penguins would come into the shore.

I took my leave of the platform, glancing behind me one last time to watch as Ashley flipped a switch and enveloped the shoreline in darkness. All around us, the penguins called their mates and that was the sound that carried me home.

Are you interested in a penguin tour with the Royal Albatross Centre? Tours run from sunset daily and start at $30/adults, $10/children. More information is available in the link above.

Like this post? Pin it!